|

|

Abstract of Graeme Lawson's doctoral thesis: 1980 |

4.1 c |

Chapters 6 & 7 |

6. Stresses & structures in design [100-137] It is argued that the most fundamental test of a musical instrument's design it not how well it meets its musical demands - how it is judged to play or sound - but whether it can play or sound at all. In stringed instruments this means especially an ability to withstand the powerful compressions, tensions, torsion and shear forces generated by the tensioning of the strings. The complexity of these forces places stringed instruments amongst the most complicated and fascinating of all products of ancient technologies. As instruments evolve the musical requirements they serve can only be realised after structural integrity has been achieved; yet this may conflict not only with practical and acoustical needs of performance but also with the wider modus operandi of performers. This chapter seeks to identify in the material record evidence of the engineering strategies which have been developed to maximise structural strength and mitigate weakness. It argues that, like high levels of investment in manufacture, evidence of special structural adaptation contributes to our understanding of the changes in musical and other behaviour which demanded them. Analysis of stresses acting on generalised structures offers a first step, revealing the structural differences between harps, lutes and lyres. Through time distinct structural adaptations appear in resonator-shells, sound-boards, superstructural beams and joints, and in the micro-engineering of bridges, especially those made of fragile materials like amber. In beams curvature is frequent, as in the ancient Greek tortoise-shell lyre where it may protect the joints from jack-knifing. Elsewhere beams adopt T and Delta-shaped cross-sections, maximising their strength-weight ratios. Wood grain is frequently oriented to structural advantage. No evidence is found of any underlying structural theory but finds reveal much shared empirical knowledge. A particular high point in musical engineering is the early medieval lyre - yet it also suffers from structural weaknesses which in experiment can lead to unwanted flexion and even catastrophic failure. Such failure is evidenced in the archaeological record in the splitting of sound-boards and snapping of tenons. Repairs and reinforcements reveal further detail. But some structural myths are also exposed. Metal 'strengthening' plates on the joints of Anglo-Saxon lyres are incorrectly placed to brace against string tension, so must have served some other purpose. Doubt is cast on putative forward-leaning superstructures of lyres shown in ancient Greek and Roman art (Maas 1974), suggesting these and other structurally inefficient types to be simply errors in depiction. Structural adaptation is invoked to explain differences between the strong-jointed cantilever structures of ancient Eastern angle-harps and the weaker-jointed, more symmetrical frames of their later Western triangular derivatives, showing their new structural forepillars to be one of a number of indications of adjustment to indigenous structural practice. 7. Practical & musical elements in design [138-165] Elimination of decorative and engineering dimensions permits for the first time a clear view of the musical needs driving these design traditions. Acoustics properties investigated by experiment include consideration of the efficacy of sound-holes in harps and later bowed instruments and their apparent absence from earlier lyres. Handling and management characteristics are also considered, particularly those related to variation in size, weight and smoothness of outline. |

The elegant smoothness of early medieval lyres of the 7th and 8th centuries is shown to render them unusually portable and may reflect the itinerancy attributed to poets in Old English texts. A need for increased efficiency in tuning may have driven the change from archaic external tuning-levers to modern tuning-pegs, a move which had already begun by Roman times, apparently involving use of socketed tuning keys from the outset. General performance characteristics evaluated include numbers of strings, whether they are arrayed symmetrically or not, and how they might have been tuned. The symmetry of Classical and early medieval lyres supports narrow intervals, and a scalar tuning is proposed for most lyres (and harps, but not necessarily lutes) up until the advent of bowing. This is consistent with a diatonic system reported by Hucbald of St-Amand in the 9th century. Images naturally show the orientation of harp tuning, but the orientation of lyre tunings has not previously been established. Evidence is adduced to argue that here too the bass string was furthest from the player. It is observed that while many early string traditions exhibit both plucking and strumming techniques the latter are especially encouraged by the smallness of surviving medieval lyre bridges. Plectra are routinely shown in images of ancient Greek lyres, but although reported in some early medieval texts they are not convincingly evidenced in either finds or pictures. Use of harmonics is encouraged in lyres and harps by extensive left-hand access to both sides of the strings. In Greek images of lyres and early medieval lyre finds provision of wrist-straps shows that both hands were intended to be used. The technical opportunities offered by the introduction of bowing (Bachmann 1964, 1969) are considered. Functional differentiation of the player's left and right hand is considered, observed similarities being used to argue that Western and Eastern lyre traditions (and indeed later Western bowed lyres) are organically connected - however distantly. East-West differences in harp-playing, however, reveal a musical discontinuity. Not only is the instrument played upside-down but images show players adopting distinctly lyre-like hand gestures - confirmed by wear patterns on extant Gaelic harps. cambridge music-archaeological research <http://www.orfeo.co.uk> |

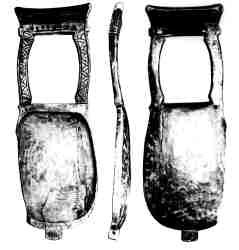

Lyre from Kravik, Buskerud, Norway, in the Norwegian Folk Museum, Oslo. Partially restored from pieces found in the 19th century in a standing farm building. Photo.: GL |

LINKS: |

1 ........ BACK TO INDEX |

4.1 d ..... CONTINUE |