|

|

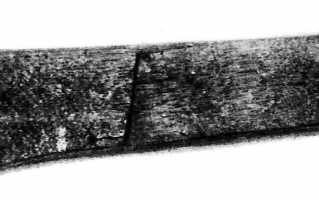

Body of the lost wooden lyre from Grave 84, Oberflacht, Germany. 6th-century. Waterlogged. |

Historiographical initiatives |

2.4 |

CMAR and the new archaeology of music |

History of an emerging science Like any emerging field of research, music's archaeology has for a long time been the preserve of the individual pioneer. Today, even as such individual efforts start to merge into coherent academic and scientific subdisciplines, the role of the individual still remains important, and indeed the pioneering origins themselves are becoming a subject of interest in their own right. From the first tentative discourse between antiquarians and music-historians in the late 18th century the trail can be followed through the dramatic discoveries of the 19th century to the engagement of modern ethnographers, iconographers, philologists and prehistorians within living memory. Believing that an awareness of its own origins is a healthy - indeed necessary - attribute of any field, CMAR is now initiating a first in-depth review of the achievements of those formative days. Musical texts, images and finds have fascinated scholars ever since the earliest modern antiquarian investigations of the eighteenth century. At first it was the texts and images which predominated; but as time went by material finds began to prove especially thought-provoking. Instruments of Ancient Greece, Rome and the Bible Lands attracted most attention, alongside those recovered from the tombs of Pharaonic Egypt. But prehistoric forms also made an early appearance, notably in Ireland and Scandinavia. Thus already in the 18th century music-historians such as Charles Burney were beginning to acknowledge their value, a process which gathered pace in the 19th century until, as the 20th century opens, we enter the modern ethnohistorical age of Otto Andersson, Francis Galpin, Curt Sachs, Friedrich Behn and Hans Hickmann (to name only a few); and in the 1950s we see a new generation of archaeologists beginning to turn their attention to music. The intended first outcome of this initiative is a biographical survey of music archaeology's varied origins, comprising studies of both the people who began the processes and some of the materials which came to shape their thinking. |

Such reviews are especially beneficial in the case of finds for which parallels remain few or even non-existent. Amongst the subjects currently under review are the lost neck of a medieval harp from County Antrim in Northern Ireland, so far still unparalleled, and a completely preserved early medieval lyre from the Swabian Jura of Southern Germany which is believed to have been destroyed in Berlin at the end of the Second World War. |

Cold case review is essentially a document-based process which attempts to draw together any surviving accounts, typically amongst collectors' manuscript journals, letters, museum catalogues and other antiquarian records. |

Detail (framed above) showing the extraordinary state of preservation, due to waterlogging, and the unsuspected quality of the surviving published image: Veeck 1931, Plate 4 B (9). |

1 |

BACK TO INDEX |

3.1 |

PUBLICATIONS |

Some of the pieces of bronze horns illustrated in John M. Kemble's posthumously published Horae Ferales: or Studies in the Archaeology of the Northern Nations (edited by R. G. Latham and A. W. Franks, 1863: Plate XIII) |

Neck of a harp from a crannog (lake dwelling) at Carncoagh in County Antrim, N. Ireland, illustrated in Knowles 1897 (Lawson 1980: Plate 28 B and Appendix A/23) |

Cold case review programme As part of its commitment to the fullest possible exploration of music's finds record, CMAR undertakes cold case reviews of documented finds from 19th- century and earlier antiquarian investigations: where either the finds themselves have since disappeared or their contexts seem inadequately reported. |

cambridge music-archaeological research <http://www.orfeo.co.uk> |