|

|

Ancient Music as Prehistory |

2.2 |

'Prehistoric' approaches to ancient musics In approaching music's distant past Cambridge Music-archaeological Research takes as its starting point the material record of archaeology: excavated finds of musical and acoustic purpose or exploitation, together with all the contextual evidence that can be gleaned from their circumstances in the ground and their situation in the wider landscape. Such an approach represents an important break from established historical approaches to ancient music. Historians and philologists of many Old World musics have, very properly, emphasized their textual dimension: exploring accounts of musical matters in the records of ancient administrators and legislators, and interpreting descriptions of music-making by writers and poets. Art historians have made musical iconography their starting point: looking at the ancient images to see how musical practices are represented there and change through time. Ethnographers have surveyed modern musical behaviours in order to model evolutionary processes that could have led to their emergence. In so doing, each discipline has naturally sought to address its own research questions; and understandably each has made use of such evidence as archaeology has from time to time been able to contribute. But with the expansion of archaeological exploration in the 1960s a new idea began to emerge: that with excavation yielding more and more musical finds it might be possible to envisage a new archaeology of music, based in the material record: not of texts or images but of relics of the behaviours themselves. In Great Britain two prehistorians, Vincent Megaw and John Coles, conducted some of the first truly archaeological studies in what might be called music's prehistory. These treated ancient music as material culture, within a framework derived from the discipline of Prehistory. The approach quickly caught the imaginations of a new generation of researchers. In Scandinavia graduate students Cajsa Lund and Christian Reimers began a major survey of Swedish archaeological collections, and a programme of archaeological experiment which was to culminate in Cajsa Lund's now famous recording Fornnordiska Klanger: The Sounds of Prehistoric Scandinavia (1984) - setting a benchmark for future practical explorations of music's prehistory. In Cambridge two of John Coles' research students, Peter Holmes and Graeme Lawson, had also embarked on doctoral studies: Peter Holmes of |

CMAR and the new archaeology of music |

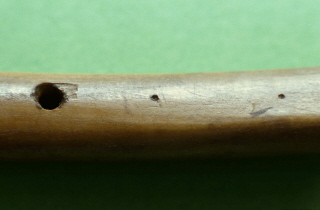

Tuning ancient musics: marking-up points on an unfinished bone pipe from Schleswig, Germany |

European Bronze Age horns and trumpets, and Graeme Lawson of ancient European stringed instruments. As these studies progressed it became apparent that 'musical prehistory' was not only drawing upon prehistory for its own purposes but had, in its turn, new things to say about prehistory. Indeed it became clear that such prehistoric approaches could usefully be applied to the musics of recent times as well: because the fine details of structure and context which archaeology preserves afford viewpoints which the documents, however detailed, very often overlook or may misrepresent. From the start, therefore, this new, finds-based 'music archaeology' began to take us in directions, and into territories, not previously travelled by more conventional approaches. Unencumbered by dependence upon a population's literacy or pictorial representation, it is capable of addressing not only prehistory but remote periods of that prehistory. In Europe today the finds have already taken us back almost to our species' first appearance here: indeed almost half way back to its anatomical origins. And they do not just cast light on music's origins: they reveal important aspects of music's evolution and the many strange paths that it has taken across the millennia. The evidence itself is susceptible of scientific analysis almost forensic in its scope and rigour. All the time our databases are expanding. We can question them in ways that are closed to the philologist or iconographer. These are not carefully worded eyewitness reports but music's own 'silent witness': its fossil record. We can use microscopy and technical analyses of different kinds to explore minute surface details and material traces, and beneath the surface too. Trends in designs, whether of instruments or sound-tools or architectural structures, inadvertently reveal to us changes in the requirements - including musical requirements - which their cultures had of them. We can look far beyond the behaviours which writers or artists thought worthy of note. If a behaviour had a material expression, and if by any quirk of taphonomy that expression may be capable of survival, there is a chance for us to find it. By such means 'music archaeology' is challenging, in a constructive way, many of the conclusions reached by more established means. Discrepancies between images and the realities they sought to represent are being actively explored. Conflicts are emerging between some ancient philosophical writings on music and the practices they purport to describe. Ancient tonal theories, previously our sole evidence for tonal practice, appear increasingly as philosophical abstractions or generalisations: true perhaps for a limited range of theoretically based traditions but not necessarily true of musical behaviour at large. And everywhere the new realities reveal themselves to be infinitely more varied and complex than expected. Today Cambridge Music-archaeological Research continues to advocate the modelling of past musical behaviours, and music's long evolution, from within the material record. Initiatives in music archaeological survey, science-based music archaeology and music-archaeological conservation science are described below. |

GL forthcoming |

2.3 |

1 |

BACK TO INDEX |

3.1 |

SCIENCE & CONSERVN. |

PUBLICATIONS |

cambridge music-archaeological research <http://www.orfeo.co.uk> |