|

|

Science & Conservation |

2.3 |

CMAR and the new archaeology of music |

Taphonomy and Conservation The extent to which objects' materials and surfaces reflect the ways they were once used is complicated by their long exposure to biological, chemical and mechanical processes in the ground, and even during their recovery and treatment. Thus while an appreciation of taphonomy, the science of decay and survival, is vital to our understanding of all such fragile traces, it is equally vital that excavators and conservators understand their nature and importance, if they are to survive excavation and preservation. |

Museums and Research Collections With ancient music's material evidence at the heart of his investigations Graeme Lawson attaches especial weight to finds-survey work and to professional liaison with archaeological colleagues in museums, in the conservation laboratory and in the field. A particular kind of survey, the regional 'blind' survey unlimited by type, proves the most effective - and economical - way of recovering new evidence from existing collections. Pioneered in the 1970s with researchers such as Cajsa Lund (Sweden) and Joan Rimmer (Netherlands), such survey subjects collections to rigorous inspection, not through their catalogues but through sight of the whole material, tray by tray, unprejudiced by previous categorisations. It is a time-consuming but rewarding process. Today, in addition to regular contributions to archaeology's primary literature of excavation reports, survey in turn enables Cambridge Music-archaeological Survey to supply technical feedback on a range of important practical museological issues. |

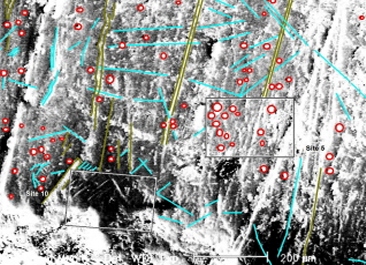

Scanning electron micrograph of the finger-hole margin of a medieval bone flute, showing various types of pitting and scratching. Scale 0.2 mm. |

GL/AMISP |

1 |

2.4 |

HISTORIOGRAPHY |

To meet this challenge CMAR engages closely with conservation scientists, promoting the special character and particular needs of music-archaeological finds, and the consequent importance of dedicated conservation regimes. Following the success of its Musical instruments: Guides to Identification for Excavators and Conservators in the early 1980s the series is soon to be reissued in a new, fully revised format. |

Shadow and fragments of the lyre from Prittlewell, Essex, in situ - setting new standards in music-archaeological conservation. Conservator: Liz Barham. © Museum of London Archaeology Service 2003. |

Music-archaeological Science The great benefit of all such finds is their susceptibility to scientific analysis. Being part of the material world we can interrogate them in the same way that planetary scientists probe the solar system and forensic scientists investigate evidence of crimes. Musical instruments of all kinds can be reconstructed and subjected to experimental tests of their engineering structures and musical capabilities. Ergonometry can point to functional implications of designs. Even landscape monuments and architectures can be subjected to detailed acoustimetric analysis. Some of the most exciting new work concerns the analysis of materials and surfaces. Timbers may be dated and even provenanced by dendrochronology, other materials by mineralogical and metallurgical analysis. Wood and bone can yield radiocarbon dates. Deposits on surfaces may indicate preservative treatments or preserve delicate traces of missing components. Remains of the musicians themselves can be explored, pathology revealing their health and stable isotope analysis of their teeth showing where they grew up. Optical and electron microscopy of bone, metal and mineral surfaces shows that they preserve traces of how some instruments were used. |

BACK TO INDEX |

cambridge music-archaeological research <http://www.orfeo.co.uk> |

Stringed-instrument tuning pegs from Wales. Medieval, animal bone. |

1993 |

Such surfaces and their wear patterns are the focus of the Ancient Musical Surfaces Project established by Graeme Lawson in 1996 (Lawson 1999 et seq.) |